First published in Converting Quarterly, Quarter 2: 2014 issue.

Written by Harper product development engineer, Tony Donato

Introduction

From the beginning of flexography – originally called aniline printing – its strength was the process’s ability to print on a very wide range of substrates in a web-fed, roll-to-roll (R2R) method. This strength has lead flexography to be the dominate process of choice for cost, quality and versatility in the packaging segment in North A merica, and it is on track to dominate package printing worldwide. What makes flexo different from other processes is the use of a relief-imaged flexible plate that – after being attached to a cylinder – receives ink from contact with a uniformly engraved roller called an anilox roll. The anilox roller originated as a full coverage gravure cylinder that was mechanically engraved into a copper layer and, after engraving, given a top coat of hard chrome plating. This served the process well, as long as it was doing simple text printing. As the users of flexography saw the potential of the process and the packaging industry experienced the impact of the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990 [1], the elements of the process improved exponentially through the 1990s, led by the use of an anilox roll that was laser engraved into a ceramic surface.

From the beginning of flexography – originally called aniline printing – its strength was the process’s ability to print on a very wide range of substrates in a web-fed, roll-to-roll (R2R) method. This strength has lead flexography to be the dominate process of choice for cost, quality and versatility in the packaging segment in North A merica, and it is on track to dominate package printing worldwide. What makes flexo different from other processes is the use of a relief-imaged flexible plate that – after being attached to a cylinder – receives ink from contact with a uniformly engraved roller called an anilox roll. The anilox roller originated as a full coverage gravure cylinder that was mechanically engraved into a copper layer and, after engraving, given a top coat of hard chrome plating. This served the process well, as long as it was doing simple text printing. As the users of flexography saw the potential of the process and the packaging industry experienced the impact of the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990 [1], the elements of the process improved exponentially through the 1990s, led by the use of an anilox roll that was laser engraved into a ceramic surface.

Because an anilox roller can be used with different imaged plates, pressure was put on the engravers to produce a longer lasting engraving surface. Initially, the mechanical engraving moved from copper and hard chrome to other metals – such as mild and stainless steels – and eventually the top layer of chrome was replaced with a thermal-sprayed ceramic top coating (see Figures 1-3). This increased surface life but still was limited in screen count and volume due to what mechanical engraving tools could be produced, and because the top ceramic coating also partially filled the mechanically engraved cells.

Introduced in the late 1980s, a new anilox-roll surface was developed that used a computer-controlled, pulsing laser that blind-hole-drilled a controlled pattern into a thermal-sprayed, Cr²O³ (chromium oxide)-coated surface. The laser-engraved anilox roller was born, and its evolution has continued moving it beyond the 550 screen-count limit of the mechanically engraved pattern to screen counts of 2,000. Today, the laser-engraved, ceramic (LEC) anilox rolls have proven themselves as the most consistent means of regulating the amount of ink film thickness being deposited onto a given substrate – guaranteeing the desired color densities.

LEC rollers apply to direct-gravure coating

With the evolution of the LEC roller, processing equipment and methods improvements have resulted in increasing the density of the ceramic, improving surface finish, providing variations in engraved geometries and – with the latest 500-watt fiber lasers – have given engravers the ability to engrave very low line screens (20 lpi) with consistent wall thicknesses and volumes to the 100-bcm (billion cubic microns) range. These improvements also have allowed the LEC roller to become used more frequently as a direct-gravure cylinder for coating, laminating, long-running patterns in product gravure, such as décor images and texts on tail-end printers that use a fixed repeat.

The advantages of chromium oxide begins with the coating thickness, the Cr²O³ being applied in a controlled-plasma, thermal-spray process that converts a granulated powder into a coating that can be applied as thick as needed, so the entire engraving is in the ceramic. This gives the engraving the advantage of having the same hardness through its entire depth instead of having only 0.0005 to 0.002 in. of hard chrome to protect the mechanically engraved cells. Note: hard chrome has a hardness of 900-1100 Hv but needs a minimum of 0.001-in. thickness to reach the hardness, and the wear resistance drops below 0.001-in. thickness.

Traditional gravure cylinders can be reprocessed into an LEC surface. First, after the old coatings are removed, the steel cylinder is coated with chromium oxide using the plasma, thermalspray method. The chromiumoxide material is a minimum of 0.005 in. thick and is ground to a T.I.R. (Total Indicator Run-out) of 0.0005 to 0.001 in., then is diamondpolished to 4 Ra to make it ready for laser engraving. The advantage of laser-engraved, ceramic cylinders is their longer life – between 10 to 20 times that of a traditional chromed cylinder.

Advantages of LECs for gravure

One of the biggest advantages of LEC is its wear resistance to the metering of steel or ceramic doctor blades and abrasive pigments, such as titanium oxide and for direct-gravure abrasive substrates. The ability to resist abrasion also allows LECcylinders to be used in traditional gravure-forward metering or where the coating station has a fixed repeat metered in the reverse-blade direction. By reverse-metering, the consistency of the coating thickness is controlled only by the cylinder volume and is not affected by the forward blade angle. Reverse metering helps to keep the process under control longer through the use of an enclosed inking chamber with fixed-blade contact angles and removes the need for an open ink bath as in traditional gravure metering. Removing the open ink bath also helps to keep the ink/coating viscosity more controllable.

The enclosed inking chamber first used in wide-web flexography has two doctor blades – metering and containment – and end seals; this allows the ink to be metered into the engravings and, at the same time, pumped to and from an ink tank that can be covered to reduce evaporation (see Figure 4).

The open pan typical of gravure requires operator skill to set and adjust the doctor-blade angles and pressure that all affect the life of the chrome plating (see Figure 5).

LEC cylinders can be used in all the gravure process variations, especially where the run length is measured in shifts and where the coating weight or finish is critical over the long run (see Figure 6A-6C).

LEC engraving variations

Because LEC cylinders get the engraving geometry from the laser-engraver software and not from a mechanical tool or stylus, LEC engraving variations are almost infinite. The software using the rotary encoder of the head stock and linear encoder of the bed can position a focused laser beam to unbelievable precision, so the cylinder surface can be blind-hole-drilled or cut in a manner that allows almost any geometric shape to be created. The controlled pulsing and placement sequence creates the surface geometry, and the power control varies the depth to give the desired volume for a given line screen.

The traditional 45-deg mechanical quadrangle shape is easily replaced with a 60-deg hexagon that will provide 15 percent more cells in a given area than the 45 deg. Packing more cells in a given area reduces the cell walls and helps in a more even distribution of a coating. The engravings (see Figures 7-15) can be closed cells in a 60-, 30-, 45-deg or elongated variation patterns; 70-, 75-deg or open cells looking like straight-lined threads; (trihelicals in almost any angle 45 deg, 89 deg) to weave like engravings that have parallel continuous walls; and variations where opposing walls look like an hour glass. Note: Not all LEC suppliers can produce all the different geometries; some are exclusive. Consult your supplier for their capabilities and the geometry that is best for your application.

Match LEC geometry to coating application

In choosing the best LEC geometry for your coating application, it is necessary to consider the pigment fl ake size and viscosity. Thinner coatings typically require closed-cell geometry, and the cell opening needs to be suffi cient to allow the pigment to tumble in and out without getting lodged in the cell. For thick coatings, open-cell geometry is most helpful to prevent air from becoming trapped in the cell as the emptied cell returns from the nip to coating/inking system. In most closed-cell applications, due to the difference in the LEC cell shape and the difference in the ceramic surface as compared to a mechanically engraved chrome (MEC) roll, the volume of the LEC will need to be higher than a chrome roll. A good starting point is 15 to 20 percent higher, but the best way to convert a MEC to a LEC is to start with a banded roll. An LEC-experienced technical support professional can review your requirements and put together a 4- to 8-band engraving that will have different geometries, as well as screen counts and volumes.

The 3D images in Figure 16 show how line screen and volume can affect the cell shape and, in the right combination, the cell walls and bottom can be shaped to help coating release and engraving cleaning.

Ceramic is very wear-resistant, so longer-life doctor blades can be used; however, the ceramic has very little impact resistance and can be chipped easily. Unlike traditional cylinders that can be somewhat repaired and re-chromed, the ceramic cylinder cannot be repaired if chipped away from the very ends. It only can be stripped and completely reconditioned. End chips can be repaired with a compatible epoxy, and this repair will help prevent the chip from growing; if the chip is in the end-seal area, this type of repair will help the life of the chamber seal. One other advantage with LEC is the availability of multiple, corrosion-resistant, bond coatings that can be applied under the ceramic to give the cylinder added corrosion resistance.

For coating applications, the LEC supplier will require the lbs/ream or coating dry thickness and process type. Ink and substrate characteristics are important as the ink – percent solids, pigment size, carrier type – helps to choose the type of engraving. For fl exo or offset-gravure application methods, 19 to 23 percent deposition effi ciency is required – a transfer roller is needed. Flexo must have a higher BCM volume. Direct gravure will use a 40 to 45 percent deposition effi ciency and less volume for the same deposition as fl exo. If available, a “smoothing bar” or off-speed reverse method removes lines and levels the coating. Wetting characteristics of the substrate also are important. Wet-out ability is needed to choose engraving type – CPI and BCM. For example, a 30- deg channel reduces pinholing on film.

Flood coating, laminations, adhesives

Continuous laser-engraved cylinders are perfect for fl ood coatings, lamination and adhesives or primer decks where the cylinder is seldom changed and the repeat stays constant. As mentioned, advantages of the ceramic engraved cylinder is it can be metered by either the traditional forward-doctoring, gravure blade system or a reverseangled, single blade or enclosed chambered inking system. The enclosed chamber application for adhesives, varnishes, primers or laminators also will help control the viscosity of the coating or ink. The LEC cylinder will last so much longer and will allow for the application of tool steel or ceramic doctor blades with a radius tip, so the coating unit’s uptime is maximized with the reduction in cylinder and or blade changes. Also, when the LEC cylinder is fitted with an enclosed chamber, coating efficiency increases due to the ability to pump the coating into and from the chamber, which helps control viscosity and also makes it easier to change coatings due to less inking equipment to be cleaned. In addition, by using a chamber the coating can be pumped from a drum where a mixer can be mounted to help keep the coating components in proper suspension.

Ceramic laser-engraved, imaged cylinders have their challenges with keeping haze to an acceptable level. The quality of the ceramic coating is very important to have less than 0.5 percent of porosity for the LEC cylinder to be used in an imaged application. Ceramic’s porosity can carry ink, which when properly polished, is not a bad thing because it can help lubricate the traditional forward-metering doctor blade as the crosshatching on a copper/chrome cylinder does. Post-engraving finishing is very important to keep haze under control and so is the blade contact angle. For LEC-imaged cylinders, the contact angle of the blade needs to be in the same range as publication gravure – 60 to 64 degs. A thin metering tip is very helpful also; it needs to be matched with the right blade coating or material. When using a thin metering blade tip, the cylinder radius needs to be close to a 1/4-in. to reduce the blade tip from work-hardening on the edges as it oscillates on and off the cylinder.

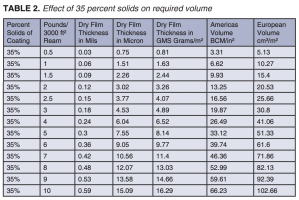

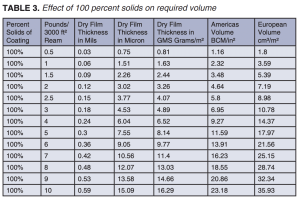

Effect of percent solids on required volume

Tables 1-3 show how the percent solids affect the required volume for a direct-gravure coating or laminating application using a LEC cylinder. All data assume a directgravure deposition efficiency of 42 percent, a 3,000 ft2 ream and 9 lbs/ gal. The tables show, in a logical manner, that as the percent solids decrease, the volume inversely increases, and for 100 percent solids energy-cured inks (EB & UV), the achievable coating thicknesses increases. For a 4 lbs/ream coatweight with only 10 percent solids, it takes almost 93 bcm; at 35 percent solids – 26.5 bcm; and at 100 percent solids – only needs 9.3 bcm.

Tables 1-3 show how the percent solids affect the required volume for a direct-gravure coating or laminating application using a LEC cylinder. All data assume a directgravure deposition efficiency of 42 percent, a 3,000 ft2 ream and 9 lbs/ gal. The tables show, in a logical manner, that as the percent solids decrease, the volume inversely increases, and for 100 percent solids energy-cured inks (EB & UV), the achievable coating thicknesses increases. For a 4 lbs/ream coatweight with only 10 percent solids, it takes almost 93 bcm; at 35 percent solids – 26.5 bcm; and at 100 percent solids – only needs 9.3 bcm.

The other issue that goes along with gravure coating is drying capacity. Just because a large volume cylinder is now available does not mean it can be used. Review the amount of drying capacity available and or what is considered the acceptable coating speed required to make the job profitable.

The other issue that goes along with gravure coating is drying capacity. Just because a large volume cylinder is now available does not mean it can be used. Review the amount of drying capacity available and or what is considered the acceptable coating speed required to make the job profitable.

LEC cylinder handling, maintenance

When using LEC cylinders in gravure applications, extra care is needed in cylinder handling. Always keep covers on the engraving and protect the cylinders from being bumped into the press frames or other corners. As previously stated, ceramic has tremendous wear resistance, but little impact resistance. When cleaning the LEC cylinders use an anilox stainless-steel brush; do not use a brass brush on ceramic. Off-line cleaning systems such as soda or media blasting, ultrasonic tanks and auto-cycle systems all can be employed, but it is always best to consult the equipment and LEC suppliers to make sure the appropriate chemicals, accessories and parameters are used.

After cleaning with any water-based cleaning system, always fully dry by rotating the cylinder, applying alcohol or use oil-free, compressed air. Drying prevents water spots, which can form on the ceramic surface in the shape of quarters on the bottom side, if the cylinder is not dry when rotation stops. In most cases, water spots will show up in the print and they are easier to prevent than remove.

Summary

The advantages of using laser-engraved, ceramic cylinders outweigh the disadvantages in applications of flood coatings, laminating and long-running images or patterns of one to three cylinders.

Advantages:

• Very long working life (10 to 20x)

• Can be metered with steel, tool steel or ceramic-coated blades

• Can be reverse-metered, single blade or chamber-inking system

• Wide range of available engraving geometries

• Closed cells or continuous channels are available

• Can be engraved from TIF (AI) files images or patterns

• Limitless combinations of lpi and volumes (BCM)

Disadvantages:

• Initial cost (2 to 4x)

• Specification correlation (stylus angle/ percent vs. lpi/BCM)

• Limited number of imaged cylinders – two to three for registered jobs

• Ceramic has very limited impact resistance

Final considerations

When using LEC cylinders for the first time, a banded cylinder may be required to match the gravure coating requirements to the laser-engraving, ceramic specifications. Finally, as for any new project, assemble an internal and external team consisting of your LEC cylinder, doctor blade and coating suppliers. This will facilitate a faster transition from traditional, mechanically engraved chrome to laser-engraved ceramic. In the proper application, you will find your coating/ laminating costs will be reduced and product quality will not be compromised and, in some applications, actually will be increased.

About the Author: Tony Donato, product development engineer, Harper Corp. of America (Charlotte, NC), holds degrees from Purdue and Winthrop Universities, has trained in TQM, ISO and environment compliance, and became FIRST-certified as an Implementation Specialist in 2011. He has 40 years of industrial experience in manufacturing and plant management, line supervision, plant and facility engineering, manufacturing engineering, production and safety training, technical customer support, application sales and product development. In 2013, Tony received the “Top Cat” Award from the Graphic Communications Dept. of Clemson University for supporting the program.

To view the original Converting Quarterly article click HERE.