The Anilox Role: Its Evolution & Adaptation to Technological Advancements

First published in FLEXO Magazine, June 2016 issue.

Written by Harper West Coast Technical Solutions Advisor, Trevor Schroeder

The Advancement in flexographic printing continues to progress through scientific testing and proper implementation of new technologies. While each respective flexographic supplier develops, markets and supports advancements within their product, the effect on the overall process is a continued trend toward higher profitability, faster printing speeds, and better product performance properties.

Advances in plate technologies and prepress screening have added to increased ink transfer, and allow for thinner ink films and larger color gamuts. Advances in ink technologies allow for faster press speeds, stronger compositions, and enhanced end use product performance. Expanded gamut, low mitigation, LED UV curable inks, and increased plate transfer all amount to better gross margin control for the converter and more considerations for their successful implementations.

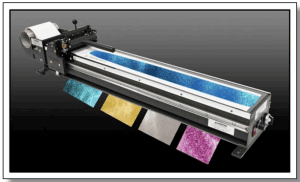

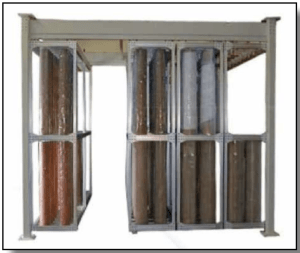

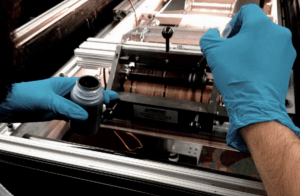

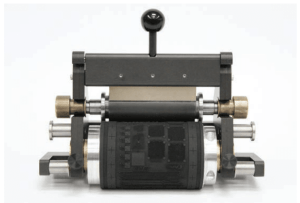

At the heart of the overall process is the anilox roll, faithfully delivering ink in concert with the ever increasing selection of doctor blades and chambers that are developed to increase press speeds.

Developments since the bygone days of rubber stamp printing are remarkable, considering the relative simplicity of the flexographic process. With so few moving parts, flexography is, in a simple word, elegant. However, much like the game golf, the simplicity seems to end there. As Arnold Palmer once stated, “Golf is deceptively simple and endlessly complicated.” Developments in any particular component impact the whole – a trend which continues to this day.

Anilox technology has always relied on small ink carrying pockets of various size and linescreen for delivery to the printing plate. Initially, these were mechanically knurled cells in copper which were subsequently chrome plated for hardness. Today, the use of chromium (III) oxide (Cr203) applied via plasma thermal spray creates a metallic, glass like ceramic structure which is able to be engraved with a laser to produce these ink carrying cells. The combination of the rapidly pulsed laser and the ability to reshape chromium oxide multiple times with laser energy is what has allowed the familiar hexagonal surface matrix we know today.

FRICKEN’ LASERS

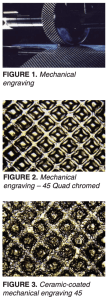

Engraving technology has advanced in step with newer lasers, faster computers and improved software. Carbon dioxide flowing gas lasers were the original choice for their power and ability to drill into chromium oxide ceramic. The carbon dioxide single pulse laser would form cells in a single, spiral pass. This was aptly named single beam, single pass technology.

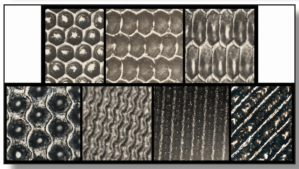

The shape of an individual cell and the cells around it is a result of the mathematical placement of laser pulses to create a desired geometric formation. With a single beam, single pass laser, the geometry of the engraving is the result of rotational and traverse speed, laser power, beam spot size and the time length of the pulses. The resulting cell shape was somewhat deep and conical, with linescreens in the range of 120 to 800 cpi.

Engraving hundred of millions of cells is not without computational challenges of its own. Anilox laser engravers use the rotational velocity, pulse length and traverse to deliver a precisely timed pulse to the ceramic coating to engrave the cells. Advances in computing power allow for single beam, multi pass, where a cell can be engraved twice – a simple idea with complete computational implementation. Delivering a pulse to create 20-u sized cell at high speed is akin to splitting a hair with a bow and arrow, out the window of a car, traveling down the interstate. Teo or more separate pulses to a single cell allow for more refined control over the final cell shape. In addition, a larger amount of ceramic could also be displaced, allowing for low linescreen, high volume coating rolls.

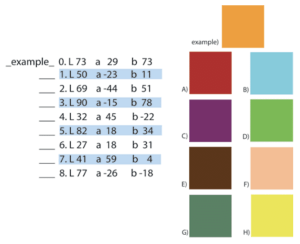

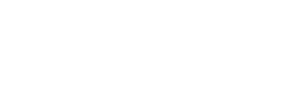

Carbon dioxide (blue) cell profiles engrave a conical, deepcell. Multi beam fiber optic engravings (red) havesteeper walls and flatter cell floors with the same volume. Both qualities promote ink transfer.

The most recent laser technology employed in anilox manufacturing is the fiber optic laser. Fiber lasers are fundamentally different than carbon dioxide and allow for a very high intensity pulse at a very high rate, making it easier to drill an exceptionally small diameter. The reduction in laser diameter allows for extremely high linescreens and yet more refined control over the cell shape. This spot size reduction, coupled with developments in laser beam delivery systems, allow the beam to be split simultaneously.

Thus, we arrive at multi beam, multi pass laser technology. Several laser pulses can be used simultaneously to finesse ceramic into shape; multiple laser passes could be used to displace a larger amount of ceramic while reducing the amount of recast at the top cell craters. These advancements helped develop a cell with a less conical volume in favor of a more rectangular floor. Cell walls are thinner and post areas (the area where three cells meet) are better formed. With the flatter floor, there is less depth for a given volume, making a more efficient cell shape; the thinner walls increase ink contact area with plate dots-both properties which contribute to better ink release.

Thus, we arrive at multi beam, multi pass laser technology. Several laser pulses can be used simultaneously to finesse ceramic into shape; multiple laser passes could be used to displace a larger amount of ceramic while reducing the amount of recast at the top cell craters. These advancements helped develop a cell with a less conical volume in favor of a more rectangular floor. Cell walls are thinner and post areas (the area where three cells meet) are better formed. With the flatter floor, there is less depth for a given volume, making a more efficient cell shape; the thinner walls increase ink contact area with plate dots-both properties which contribute to better ink release.

ANILOXES & FIRST

The fundamental purpose of an anilox is to deliver the correct an10unt of ink for a desired film thickness at printable viscosity, while delivering it to the plate with minimal impression. There are several additional considerations including longevity, resistance to damage and important printability aspects, such as a reduced chance of cell plugging and performance at high speeds. Banded roll trials are still the gold standard for identifying job and graphics specific variables. Tonal value increase can be considered while ink targets are hit (or slightly exceeded). In expanded gamut printing, chroma can be maximized before hue shifts away from targeted angles.

“At the heart of the overall process is the anilox roll, faithfully delivering ink in concert with the ever increasing selection of doctor blades and chambers that are developed to increase press speeds.”

As more and more firms adopt expanded gamut and fixed palette color, selection and application of technological advancements becomes more critical. Subtle differences with each part of the process can have a large impact on final print quality. Fortunately, the FIRST (Flexographic Image Reproduction Specifications& Tolerances) methodology provides an essential framework for successful implementation of these new technologies.

The initial step in the FIRST methodology is optimizing the printing press. This is a task that should not be looked at as something done in the past; rather, ask the question, “Is the press optimized in its current state, today?” Anilox engraving selection and specifications, substrate, ink, coating, mounting tape and plate materials are all job specific print variables that require optimization. Changes from 4-color process to expanded gamut require re optimization with the new ink systems. Changes from conventional UV to low migration require the same process, as ink pigment selection is limited. Selecting an anilox engraving for these new technologies requires testing, data collection and evaluation.

With the small number of moving parts, a properly metered ink film is critical to success. The anilox roll and doctor blade are a formidable choice for the application, as they are able to meter ink with precision at high speeds. Consistency of the anilox engraving, its surface flatness, longevity and maintenance directly impact the quality of the flexographic process in a production setting.

OUR SAVIOR, THE 60

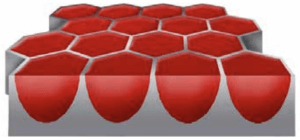

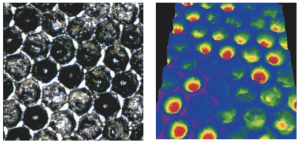

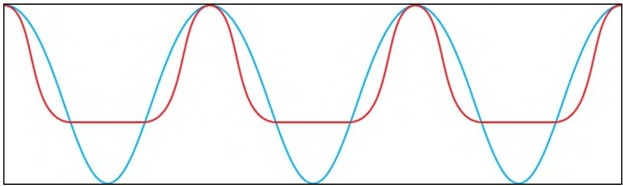

A 60 degree engraving with the familiar honeycomb structure. Cell volume uniformity is responsible for consistent ink film thickness. and walls provide support forfine plate features, such as highlight dots.

It is no coincidence the 60 degree cell has seen such prolific success in the laser engraved anilox industry. The honeycomb conjecture states the honeycomb grid is the most efficient way to divide a surface into equal areas with the least possible perimeter. Although the honeycomb geometry has been discussed since Varro in 36 BC, it wasn’t until 1999 when the conjecture was proven mathematically by Thomas C. Hales. Similarly, the densest configuration of circles in a two dimensional (2- D) plane is when the center of the circles rest on a hexagonal lattice. This can be seen in a game of pool as the billiard balls are racked.

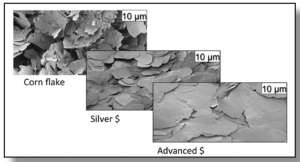

Laser engraved cells start as a circle; we can think of a lone anilox cell as a crater in the surface of the moon. Energy from the laser causes a microscopic explosion of ceramic; absorbed energy from the laser heats the ceramic and causes it to flow to the surface. This process, called recasting, is the foundation to the laser engraving process. By packing these naturally forming “craters” into a hexagonal lattice, we are left with the highest density of equally sized cells on the surface of the anilox. The smallest possible wall area increases the contact between the plate and the ink contained in the cells. Sufficient wall area is needed to support highlight dots and prevent over-inking, which can lead to unnecessary tonal value increase.

Flexography has the ability to print a wide variety of specialty inks and coatings on a very diverse range of substrates. This is a key advantage to the competitive edge the flexographic market has seen when compared to other traditionally more expensive print processes. Many specialty applications should be approached as such; testing and evaluating new product offerings allows for the appropriate implementation of technological innovation.

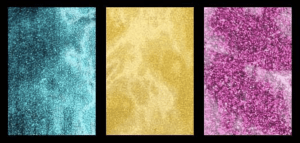

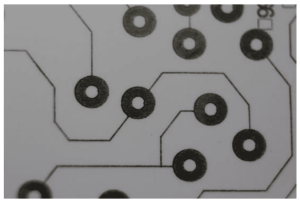

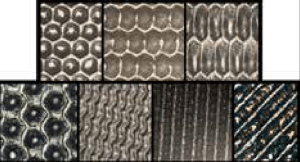

While the hexagon is geometrically efficient, there is not always a need to support fine plate features, such as highlight dots. When appl)1ng adhesive or coatings, or where particles are required to transfer in suspension, fewer walls can be advantageous. This can be accomplished with channels and trenches. By reducing the number of walls, there is more room for particles to flow in and out of cells. Glitters, adhesives, encapsulated compounds, functional and electrically conductive inks all require special consideration other than the appeal of a highlight dot. Ink film thickness is one of many critical factors to success in these applications.

Some adhesives, including latex and other water based compounds, require gentle application to prevent foaming or activation. Trihelical and channeled engravings usually provide the qualities needed to outperform in these applications. Encapsulated inks need to make it to the substrate without breaking to allow for functionality at a later time. Electrically conductive inks require special consideration, as conductivity of the printed line is heavily dependent on its application to the substrate. Breaks in the line mean failure for the circuit-an unforgiving consequence in an expensive application.

THE NEW NORMAL

With new laser technology, we see unprecedented control over the engraVIng process. Shaping cells with a laser is a more delicate finesse, rather than a controlled explosion. While the theory remains the same, improvements in laser technology and computational ability have allowed for higher linescreens with improved cell shapes. This level of control allows for the consistency needed for expanded gamut and fixed palette printing.

To harness the most benefit from new flexographic technologies, proper implementation is critical to success. Testing and evaluation is the means to establish the correct foundation to support the rest of the process. When testing, always create a team that includes your anilox, ink, plate, substrate and blade suppliers to make sure you are incorporating the latest flexographic developments. Revisit the fundamentals as part of the project to ensure your current process is optimized

today for a successful tomorrow.■

About the Author: Trevor Schroeder is the West Coast technical graph ics advisor for Harper Graphics Solutions, a division of Harper Corporation of America. He holds a Bachelor of Science degree in graphic communication from California Polytechnic State University mid a Master of Science in print media from the Rochester

About the Author: Trevor Schroeder is the West Coast technical graph ics advisor for Harper Graphics Solutions, a division of Harper Corporation of America. He holds a Bachelor of Science degree in graphic communication from California Polytechnic State University mid a Master of Science in print media from the Rochester

Institute of Technology. His past work has focused on adopting digital printing technologies in conventional printing and converting businesses; he currently provides technical anilox support to flexographic printers and converters in both narrow web and wide web markets on the West Coast. He may be reached attsclzroeder@harperimage.com.

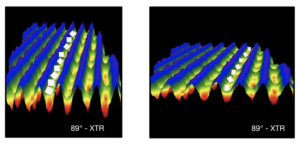

As an example, if the coating is very thick and is going to be applied to an uncoated substrate, then it makes sense to use large cell engravings, such as the 45 degree quad, 70 degree hex, KatRon or one of the channel engravings. Uncoated substrates will necessitate heavier coatings because of the absorbent characteristics of the material. Weave engravings, 30 degree channel, 45 degree trihelical, 60 degree XTR, 70 degree XTR or 89 degree XTR; channel engravings naturally will lay down lots of product due to the continuous open channel patterns. Some very thick coatings will need the channel engravings in order to achieve the recommended coat weight. Coatings require thicker application and, naturally, the larger open engravings are a good fit. With the information provided on the TDS and a Coating Application Worksheet, your anilox supplier will be able to recommend the correct anilox specification for your needs.

As an example, if the coating is very thick and is going to be applied to an uncoated substrate, then it makes sense to use large cell engravings, such as the 45 degree quad, 70 degree hex, KatRon or one of the channel engravings. Uncoated substrates will necessitate heavier coatings because of the absorbent characteristics of the material. Weave engravings, 30 degree channel, 45 degree trihelical, 60 degree XTR, 70 degree XTR or 89 degree XTR; channel engravings naturally will lay down lots of product due to the continuous open channel patterns. Some very thick coatings will need the channel engravings in order to achieve the recommended coat weight. Coatings require thicker application and, naturally, the larger open engravings are a good fit. With the information provided on the TDS and a Coating Application Worksheet, your anilox supplier will be able to recommend the correct anilox specification for your needs. From the anilox recommendation side, the critical criteria will be the particle size. A good rule of thumb is to keep the cell opening a minimum of twice the size of the largest particle size. For example, if you are applying pearlescent inks with 15-µ. to 20-µ. size particles, your anilox should have, at the minimum, an opening of 40-µ.

From the anilox recommendation side, the critical criteria will be the particle size. A good rule of thumb is to keep the cell opening a minimum of twice the size of the largest particle size. For example, if you are applying pearlescent inks with 15-µ. to 20-µ. size particles, your anilox should have, at the minimum, an opening of 40-µ.