Improve Performance Reliability While Reducing Waste

First published in FLEXO Magazine, January 2019 issue.

Written by Harper Technical Solutions team member, Richard Hernandez

When I was first learning how to run a press, one of the biggest things I could remember thinking was, “How am I supposed to know how these different anilox rollers print?” I would watch all the veteran operators switching out anilox rollers, and they knew exactly which one to drop into press for each job. How did they learn it?

They learned from trial and error. For the development of my understanding, it was much the same. As time went on, I figured out how to use the anilox volumes to my advantage and knew that some jobs would take this anilox, and others would run better with that one. It was all part of “learning the trade.” There had to be a better way to know which one to use, and a better understanding of what it took to obtain reliable performance.

I would like to take the opportunity to discuss how to get reliable performance and a basic understanding of the anilox, while giving an in-depth look at how to get your shop’s ink department and presses correlated, anilox rollers identified, and how to keep things organized and maintained to help you reach the full potential of your anilox rollers. In turn, this will help keep your waste down, help to promote color consistency, and keep production time up.

LINESCREEN, VOLUME & GEOMETRY

Linescreen

Understanding linescreen, volume and geometry, and how they work together is the beginning step to consistent, quality printing.

You may have certain artwork or a certain account whose print dynamics always seem to be a problem when running on press. The simplest solution could be that you are running a plate, anilox, and ink combination that is not made up of the optimum materials for that application. Locking down your anilox selection is where to start.

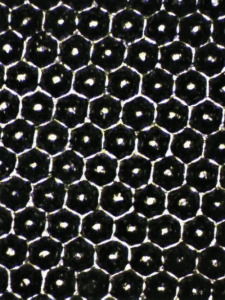

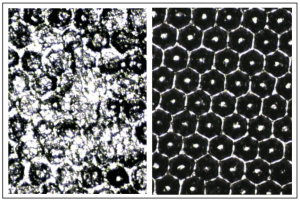

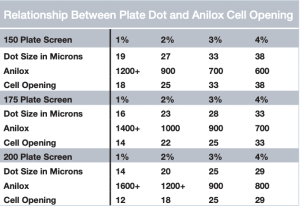

How does line screen play a role in the anilox? The line screen provides the cell opening on the surface of the anilox (see Figure 1). The line screen is defined by how many cells are present per linear inch on the roll (LPI). A properly selected line screen does two things: It allows for distribution of volume without compromising cell quality, and it supports the printed dot. When running artwork like 4-color process, a high line screen is used to help support the low dot percentages, also known as highlight screens.

Figure 1: The line screen is defined by how many cells are present per linear inch on the roll (lpi).

Volume

Historically, because the inks are formulated to hit color with thin ink films, your volume will not need to be high. Pairing more open

cells (lowering line count) with a set volume provides a greater deposit efficiency and puts more ink on the plate. The wider opening can be useful in specialty applications like particle transfers. Particle size would then dictate required volume.

Another way the LPI helps is by supporting the printed dot. Knowing the line screen of your artwork and what look you are going to achieve is how you will determine the LPI of your anilox. If you have a high line of artwork, you do not want a low line screen anilox because your dots on the plate will over-ink or under-ink instead of having ink evenly distributed to the plate dots. This will cause the bridging of dots and dirty print since too much ink is distributed. One thing to keep in mind is that the LPI of an anilox does not change with wear. It is always consistent. The only time the line screen will change is when you send it in to be remanufactured and request a different LPI.

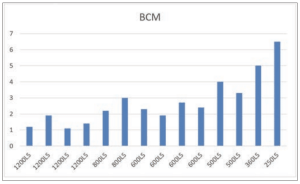

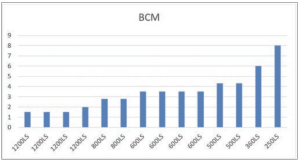

How is volume a factor in anilox selection? Volume is the amount of ink contained in the cells of a defined area (see Figure 2). This is

measured in BCM. A frame of reference will help you scale the concept of the micron: Take one human hair and look at a cross-section and divide from one side to the other into 100 equal width pieces.

Each equal width is one micron. A cell volume of 0.5-2.0 BCM is used along with a high line screen. With a high line screen, not too much ink is needed because you are typically printing fine screens without solids. A volume of 5.0-10.0 BCM is a deep cell, which will hold a lot of ink that will be distributed to the plate. These are typically used for varnishes, coatings, and whites.

You would use these volumes with a 300 LPI to 150 LPI anilox where full solids and complete coverage are needed. In many cases, the volume will be dictated by the ink supplier because formulations are dialed in to specific volume expectations. Always consult with the ink supplier to better understand the needed volumes and why. Volume can change because the BCM will be affected by wear and the cleanliness of cells. As an anilox wears down, the cell will get shallower and not carry as much ink as it did when it was new. Plugged cells immediately lower volume and can only be remedied by a thorough cleaning.

As you can see, the LPI and BCM of an anilox are major factors in how much ink will be distributed to the plate. Both play off each other and cannot work independently. But there is one more factor in your anilox identity—the geometry of your anilox.

We know how the LPI and BCM of an anilox play a role in print. But what is the best way to be assured that the ink is distributed from the cells? The geometry of the anilox is the answer.

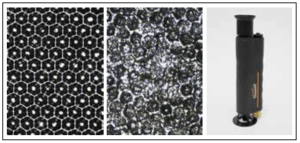

Geometry

There are so many ink systems in the industry now to help catch the eye of the customer that converters need to be sure they have the tools that can create the expected look. Some coatings are designed to be thin in consistency and others very viscous; there are different geometries that release ink in different ways to accommodate the viscosity. Hexagons, channels, elongated cells, trihelical designs, and 45-degree quads are just a few engravings that are offered to help with converter applications (see Figure 3). Some geometries are universal in application, like the 60-degree hexagonal. Others have niche applications but are more effective. Typically, thin viscosities perform better with enclosed cells and higher viscosities perform better in channel arrangements.

For coatings and inks that have never seen a flexographic press, these often need to be tested with a banded roll to dial in the right engravings. There certainly are exceptions to every rule, so speak with your anilox supplier’s regional technical support about engravings they offer and how they can help.

Figure 3: Hexagons, channels, elongated cells, trihelical designs, and 45-degree quads are just a few engravings that offer help with converter applications.

You will also want to know the needs of your plate material, ink, and artwork, and include their representatives in selecting the correct anilox rollers.

Anilox Audits

The first thing that needs to be asked is, “What is the current state of your anilox inventory?” If you were to walk your shop floor, chances are operators will have their own go-to anilox rollers. They will have a good gauge on their anilox performance, but this understanding must be taken to a higher level to meet pressroom needs. This could potentially be the originator of any color inconsistencies you might be experiencing during a color match. But how do we find out the condition of our anilox rollers? Two words—anilox audit!

Anilox audits are a great tool that will help you identify the three main components we have discussed as well as the anilox condition, so you can understand better what you have and the role each anilox can best play in your production environment.

An audit will also help in identifying which anilox rollers are damaged. A damaged anilox will have many signs, and with the help of your anilox supplier, you can identify the sources of damage and eliminate them. Chipped edges, score lines, worn cell walls, broken cell walls—these are just a few that can be brought to light by an audit. There is nothing more frustrating for printers than to have an otherwise perfectly good engraving get needlessly damaged and render it useless.

- Chipped edges are usually caused by handling. Bringing an anilox in and out of the press and hitting the press frame is a good example. Another way to get chipped edges is when moving a roller into storage, sliding the sleeve or roll to the back or

bottom of a rack, and making forceful contact. A doctor blade unit, sling guard or chamber not properly attached or inserted could also be a culprit. Additionally, corrosion can also loosen the bond between the ceramic and the base and allow the ceramic to flake away

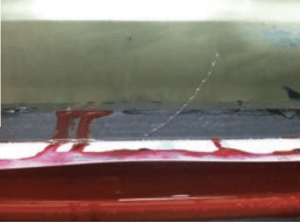

bottom of a rack, and making forceful contact. A doctor blade unit, sling guard or chamber not properly attached or inserted could also be a culprit. Additionally, corrosion can also loosen the bond between the ceramic and the base and allow the ceramic to flake away - Score lines are a tricky defect because they may or may not show in print, and finding the source can be difficult without assistance. Sometimes they are not deep enough to see in the print but are readily identified visually. Sometimes they fall right in the print area and cause an undesired print quality. Identifying the sources of contamination that get in the ink and between the blade and anilox, causing the scoring, is a task with which your anilox supplier can help

- Worn cell walls will cause an ink color to print lighter than what came out of the ink department and should be taken out of rotation. Wear can come naturally from use, but you would also have to consider blade pressure, blade holding equipment, and abrasive inks (see Figure 4). One of the most important functions of the anilox audit is to identify worn rolls and get them out of circulation without resorting to press trial and error

- Broken cell walls will cause the ink to print dark spots. If you have a 700 LPI anilox that has broken cell walls, those cells go from 700 to potentially 500 in those areas, meaning lost dot support and unwanted increases in volume where those spots are located. An operator could be chasing an issue for which he or she will not find an easy solution

Another way an audit will help is by identifying the line screen and volume of those few anilox rollers that are not marked. We all have seen anilox rollers that are older and have had their identifying marks worn down and made illegible. This will also be helpful in identifying where the proofer roll in your ink department is printing.

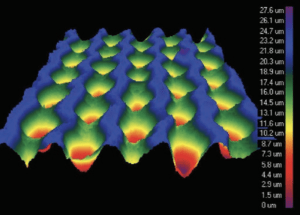

Figure 5: After an anilox audit, you will have an echotopography digital volume (EDV) value and 3D image of every anilox to review.

When the audit is graded and returned to you, you will have an EDV value (echotopography digital volume) and a 3D image of every anilox that you can then review and determine which should be cleaned and returned to inventory, monitored in future use, and which ones should be removed and replaced (see Figure 5). EDV is the measured volume of BCM.

If you own anilox rollers that are scored, have chipped edges, or are dinged, you may want to consider replacing those as well. These are factors that can cause print defects. If the doctor blade gets pulled back due to a chipped edge, it may look like a gear mark. A scoreline or ding can cause a void on a full reverse print on an anilox that otherwise matches the color perfectly. Those are just a few problems that could come about from damage that is visible. An anilox audit helps identify both issues that are visible or not visible to the naked eye.

When the anilox base condition is salvageable, you have the option of remanufacturing those engravings as well.

Achieving the full potential of your anilox inventory starts with understanding the linescreen, volume and geometry, then partnering that knowledge with proper inventory management and the useful tools the anilox audit provides. Who would have thought that all this information could have come from an anilox audit?

Knowing the components of an anilox, and how they play a role in your application, will help your workflow move smoothly out your shipping doors.

About the Author: Richard Hernandez is a sales/technical service representative – Western Region for Harper Corporation of America.

About the Author: Richard Hernandez is a sales/technical service representative – Western Region for Harper Corporation of America.

He brings more than 24 years of extensive experience in the printing industry with six years in offset printing and 18-plus years in flexography. Within that time, he has gained extensive knowledge of Webtron, Nilpeter, Comco, and Mark Andy Inc presses, as well as A.B. Dick and Heidelberg, offset presses. Richard began his flexographic career at Los Angeles Label, which led to production lead and supervisory experience at The Label Co, and Paradigm Label in California. Prior to arriving at Harper, he was the print manager at Precision Label, which helped him excel in his color matching, team member training and mentoring, and troubleshooting skills. While there, he also assisted with the R&D and product development that helped drive the company into industry-leading trends.

To view the original FLEXO Magazine article click HERE.